Writing Interactive Fiction - The Wonderful World of Text Adventure Games

Text adventure games, now more commonly known as Interactive Fiction, were popular in the early days of home computing, and have continued to find an audience even today. Learn about the origins of this genre of game, and try your own hand at writing interactive fiction with some great tools to make your writing easier and reduce dead-end storylines.

In 1976, the first version of Willie Crowther's Colossal Cave Adventure was released, which is widely credited as being the first example of interactive fiction computer game. Interactive fiction has been defined as "a unique form of computer-based storytelling which places the player in the role of a character in a simulated world, and which is characterized by its reliance upon text as its primary means of output and by its use of a flexible natural-language parser for input" (Maher, 2006). Colossal Cave Adventure was expanded by Don Woods at Stanford to make it more playable, and with those changes, the game became widely distributed on ARPANET, and later on BBS networks (Maher, 2010). It was so popular among the computer users of the time that, "those who encountered it at the time joke that computing was set back two weeks while everyone who could run Adventure spent that time solving it" (Montfort, 2007).

In 1976, the first version of Willie Crowther's Colossal Cave Adventure was released, which is widely credited as being the first example of interactive fiction computer game. Interactive fiction has been defined as "a unique form of computer-based storytelling which places the player in the role of a character in a simulated world, and which is characterized by its reliance upon text as its primary means of output and by its use of a flexible natural-language parser for input" (Maher, 2006). Colossal Cave Adventure was expanded by Don Woods at Stanford to make it more playable, and with those changes, the game became widely distributed on ARPANET, and later on BBS networks (Maher, 2010). It was so popular among the computer users of the time that, "those who encountered it at the time joke that computing was set back two weeks while everyone who could run Adventure spent that time solving it" (Montfort, 2007).

As home computers emerged on the marketplace, many companies produced commercial text adventures to appeal to these new users. With most small enough to fit comfortably on a floppy disk, text-based games were ideally suited for these early computers with limited memory and storage capacity. One company, Infocom, made a name for itself with the powerful parser and engaging stories behind their commercial titles.

As home computers evolved so did the games played on them, and soon text adventures were largely left behind as graphics-based games became the norm. Still, there has always been a small fan-base keeping interactive fiction alive. Not only does the literary nature of the best interactive fiction games appeal to story-lovers, but the simplicity of the programming required to make a basic text adventure also has meant that for many years the first program new and aspiring developers created was an interactive fiction game.

Today, the emergence of voice-activated smart assistants like Google Home and Amazon's Alexa is creating new possibilities for interactive fiction in audio form. Modern game development companies building nothing short of literary masterpieces are also reviving the art of interactive fiction for many fans. These games often enhance the experience with sound effects and soundtracks, but still rely solely on text to keep the story moving (Montfort, 2007). On new technologies these new games are tremendously entertaining, and add a social element generally missing from interactive fiction; an evening playing the "Escape the Room" Alexa skill with friends is as enjoyable as any graphics-based game we've played.

To get a taste of the number of interactive fiction games available, spend some time browsing through the aptly-named Interactive Fiction Database. It has nearly 10,000 games dating from the early 1990s through to today, with ratings and reviews by members to help you find the best of them. It also hosts an Annual Interactive Fiction Competition, where you can submit your own stories, or search out new, original, branching fiction with a maximum play-time of 2 hours.

In its heyday, a number of relatively well-known writers tried their hands at interactive fiction, including Scott Adams, Robert Pinsky, and Roger Zelazny. The titles from these literary figures were of varying quality, often due to poor game design rather than literary quality (Kaplan, 2010). Others demonstrate the dangers of trying to treat interactive fiction in the same manner as writing a novel. The result is often not playable.

Writing a work of interactive fiction is something that requires a different thought process than linear fiction writing. According to Graham Nelson, "An adventure game is a crossword at war with a narrative. Design sharply divides into the global - plot, structure, genre - and the local - puzzles and rooms, orders in which things must be done." Nelson wrote a list of guidelines for interactive fiction designers to help them respect what he called the self-evident rights of the player. These include not being killed without warning, not to be given unclear hints, to be able to win without knowing the future, or having died first, and not being tied to a poor parser that accepts only specific verbs (1995).

If you've got an interactive story you'd love to write, there are some really nice software tools to help you make the transition. Five of the best are listed below:

Twine

https://twinery.org

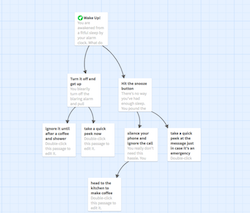

No discussion of interactive fiction is complete without mentioning Twine. It's the free, open-source, go-to software for interactive fiction. Twine uses an interface a little like post-it notes on a wall, with each option represented by one note with one or more choices branching off each subsequent slide.

No discussion of interactive fiction is complete without mentioning Twine. It's the free, open-source, go-to software for interactive fiction. Twine uses an interface a little like post-it notes on a wall, with each option represented by one note with one or more choices branching off each subsequent slide.

For ease of use, it absolutely can't be beat. To create a branch from one note to the next, you simply need to enclose your text in two square brackets [[ ]]. There are also more advanced options for creating macros and hooks in your text, and you can use markup and HTML tags to style your output.

Twine is available for all platforms, and can even be run as a web-app for users running Chrome OS. The output is an HTML/Javascript file that you can style and edit both inside and outside the Twine program.

ChoiceScript

https://www.choiceofgames.com

ChoiceScript is a programming language used by the interactive fiction development company, Choice of Games for their own critically-aclaimed games. While there is no graphical interface, ChoiceScript can improve upon more traditional text-based games as game writers have the ability to add variables which can work in the same way RPG stats developed in the early part of the game can help or hinder the player throughout the rest of the game's challenges.

If you write your interactive fiction in ChoiceScript, Choice of Games will host it for you, giving you a royalty on revenues. Or you can submit your completed work to their Interactive Novel contest and win $5,000.

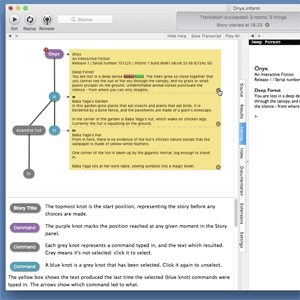

Inform

Inform

http://inform7.com

Inform is a design system for interactive fiction designed to help you write your adventure game in plain English. Inform can be run on Windows, Mac and Linux, and is widely used in education because of its accessibility to non-programmers.

While non-technical people and educators might like it for its natural language programming, the real strength of Inform is in its extensions, which allow interactive fiction writers to add things like physics, randomness, combat and dialogue to their adventures.

Ink/Inky

https://www.inklestudios.com/ink

Ink is a powerful scripting language that's also easy to use for writing interactive branching fiction. Inky is the editor you can use to write, play and test your stories. Using Ink to write an adventure game will feel quite natural to anyone who has used Markup to style their text. A few simple characters to indicate whether the text you're typing is a 'knot', 'divert', or 'choice' is all you need to start creating.

Though it is very easy to begin with Ink, there are also some advanced scripting functions that will allow you to create different types of choices, add variables, and use math and logic to enhance the replayability of your game.

What sets Inky apart is that it integrates into the Unity game editor so you can take your simple text game and turn it into something more graphical quite seamlessly.

Quest

http://textadventures.co.uk/quest

Quest is a deceptively thorough interactive fiction creator that is available as a download for the Windows operating system, or used as a web-based application. While it's easy to start writing a pure text adventure, you can easily add scripts, images, audio or even videos to your story through the easy-to-use interface.

Quest is a deceptively thorough interactive fiction creator that is available as a download for the Windows operating system, or used as a web-based application. While it's easy to start writing a pure text adventure, you can easily add scripts, images, audio or even videos to your story through the easy-to-use interface.

The program is licensed under the very permissive MIT license, so you can feel free to sell your Quest-created stories, change the Quest source code to work the way you want it, or even embed the code into your own commercial projects.